Zombie Ship Reveals America’s Strategy in the Shadows of the Oil Fleet

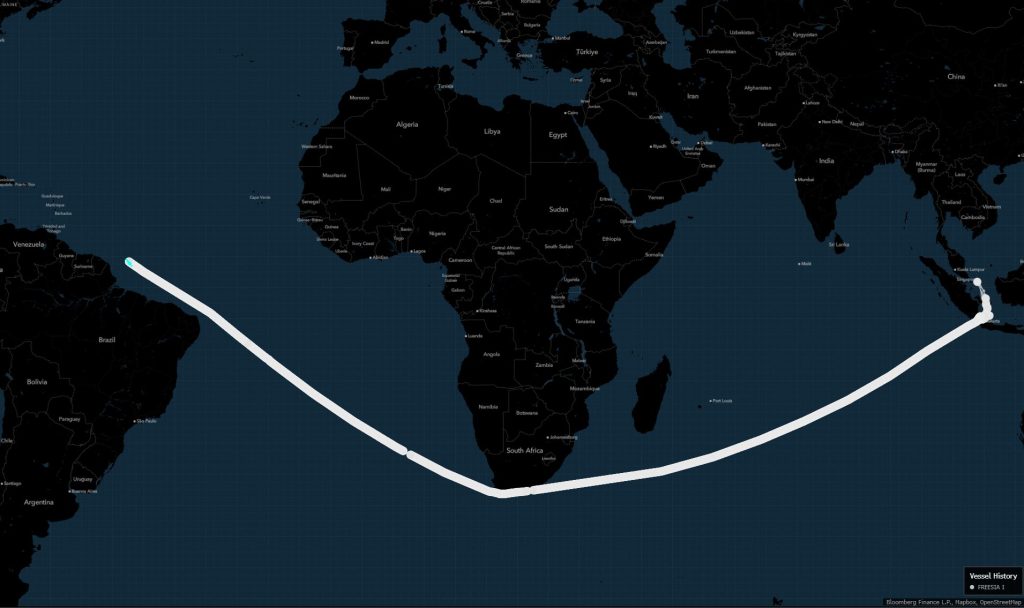

A 27-year-old crude tanker, reportedly scrapped in 2021, is set to arrive in Venezuela late this week, as indicated by ship-tracking data. This incident exemplifies how the South American nation continues to sustain its beleaguered oil industry.

The vessel, known as Freesia I, is likely a “zombie vessel,” meaning it is another tanker masquerading as a dismantled ship. This strategy is sometimes used by vessels transporting sanctioned oil to obscure their routes and cargoes.

Venezuela’s oil sector, once a global leader, has suffered greatly due to years of sanctions and underinvestment. Nevertheless, it has managed to maintain exports, primarily to China, utilizing some of the oldest and most obscure tankers in the global fleet. This maritime lifeline is crucial for both the economy and the government of President Nicolás Maduro.

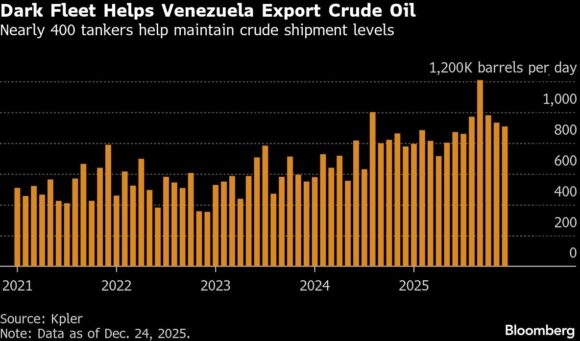

So far this year, Caracas has shipped nearly 900,000 barrels per day, according to analytics firm Kpler. While this figure is a mere fraction of past exports, it has prompted the Trump administration to enforce some of the most stringent sanctions to date.

“Venezuela has been remarkably effective at masking both the origin and ownership of crude, thereby evading financial and trade-related controls,” stated Dimitris Ampatzidis, a senior risk and compliance analyst at Kpler. “This has led Washington to shift from purely financial measures to physical disruption.”

U.S. forces have targeted alleged drug-smuggling boats in the Caribbean and have pursued or boarded three tankers near Venezuela since early December, including one non-sanctioned vessel. This marks a significant escalation in U.S. efforts, which aim to deter illicit activities and signal a desire for regime change in Venezuela. President Donald Trump has also indicated that the U.S. would retain any seized crude.

“While the U.S. has sanctioned numerous vessels and organizations, it hasn’t stopped the flow of oil. Physical boarding is the next step,” remarked Mark Douglas, a maritime domain analyst at Starboard Maritime Intelligence. “This is a clear message that falsifying locations and documentation no longer provides protection; it now makes you a target.”

Despite these tanker seizures, oil traders remain largely unfazed regarding supply disruptions, as the market braces for a global surplus. U.S. oil prices have remained relatively stable amid thin trading since tensions escalated two weeks ago.

From a dark fleet of approximately 1,500 vessels—often aged, typically uninsured, and owned by shell companies—Venezuela relies on nearly 400 ships, according to TankerTrackers.com.

These tankers engage in various practices typical of the dark fleet to obscure their movements and ownership, including spoofing, which involves using fake locations. Like Freesia I, they sometimes assume the identities of other, often dismantled, ships.

The vessel known as Freesia I was at Venezuela’s José oil-export terminal in early May. It began its latest journey in Southeast Asia in November, indicating it would arrive at the Amuay port in Venezuela on December 26, likely to take on a new cargo. It later changed its destination to “High Sea” before turning off its transponder entirely on Tuesday, near French Guiana.

Spoofing is also prevalent. The Skipper, the first Venezuelan tanker targeted by U.S. forces, was using this tactic when it was captured earlier this month. The 20-year-old tanker had indicated through tracking systems that it was idling off Guyana, but satellite images revealed it was docked at the José port on November 14.

This suggests the ship had been manipulating its signals, revealing its true location only on the day of the U.S. seizure.

At the time of its seizure, the Skipper claimed to be sailing under Guyana’s flag, a claim disputed by the South American nation. Ships must be registered with a specific country’s flag registry, which enforces safety and crew welfare standards. Many vessels in the dark fleet resort to flags of convenience or false registrations to evade inspection.

Venezuela’s regular dark fleet tankers are typically supplied by other countries, as Caracas lacks the financial means to maintain its own fleet and cannot depend on an existing fleet that is too small and outdated.

Top graphic: The tanker identifying as Freesia I recently indicated it would arrive in Venezuela by December 26, 2025.

Copyright 2025 Bloomberg.

Interested in Energy?

Get automatic alerts for this topic.

A 27-year-old crude tanker, reportedly scrapped in 2021, is set to arrive in Venezuela late this week, as indicated by ship-tracking data. This incident exemplifies how the South American nation continues to sustain its beleaguered oil industry.

The vessel, known as Freesia I, is likely a “zombie vessel,” meaning it is another tanker masquerading as a dismantled ship. This strategy is sometimes used by vessels transporting sanctioned oil to obscure their routes and cargoes.

Venezuela’s oil sector, once a global leader, has suffered greatly due to years of sanctions and underinvestment. Nevertheless, it has managed to maintain exports, primarily to China, utilizing some of the oldest and most obscure tankers in the global fleet. This maritime lifeline is crucial for both the economy and the government of President Nicolás Maduro.

So far this year, Caracas has shipped nearly 900,000 barrels per day, according to analytics firm Kpler. While this figure is a mere fraction of past exports, it has prompted the Trump administration to enforce some of the most stringent sanctions to date.

“Venezuela has been remarkably effective at masking both the origin and ownership of crude, thereby evading financial and trade-related controls,” stated Dimitris Ampatzidis, a senior risk and compliance analyst at Kpler. “This has led Washington to shift from purely financial measures to physical disruption.”

U.S. forces have targeted alleged drug-smuggling boats in the Caribbean and have pursued or boarded three tankers near Venezuela since early December, including one non-sanctioned vessel. This marks a significant escalation in U.S. efforts, which aim to deter illicit activities and signal a desire for regime change in Venezuela. President Donald Trump has also indicated that the U.S. would retain any seized crude.

“While the U.S. has sanctioned numerous vessels and organizations, it hasn’t stopped the flow of oil. Physical boarding is the next step,” remarked Mark Douglas, a maritime domain analyst at Starboard Maritime Intelligence. “This is a clear message that falsifying locations and documentation no longer provides protection; it now makes you a target.”

Despite these tanker seizures, oil traders remain largely unfazed regarding supply disruptions, as the market braces for a global surplus. U.S. oil prices have remained relatively stable amid thin trading since tensions escalated two weeks ago.

From a dark fleet of approximately 1,500 vessels—often aged, typically uninsured, and owned by shell companies—Venezuela relies on nearly 400 ships, according to TankerTrackers.com.

These tankers engage in various practices typical of the dark fleet to obscure their movements and ownership, including spoofing, which involves using fake locations. Like Freesia I, they sometimes assume the identities of other, often dismantled, ships.

The vessel known as Freesia I was at Venezuela’s José oil-export terminal in early May. It began its latest journey in Southeast Asia in November, indicating it would arrive at the Amuay port in Venezuela on December 26, likely to take on a new cargo. It later changed its destination to “High Sea” before turning off its transponder entirely on Tuesday, near French Guiana.

Spoofing is also prevalent. The Skipper, the first Venezuelan tanker targeted by U.S. forces, was using this tactic when it was captured earlier this month. The 20-year-old tanker had indicated through tracking systems that it was idling off Guyana, but satellite images revealed it was docked at the José port on November 14.

This suggests the ship had been manipulating its signals, revealing its true location only on the day of the U.S. seizure.

At the time of its seizure, the Skipper claimed to be sailing under Guyana’s flag, a claim disputed by the South American nation. Ships must be registered with a specific country’s flag registry, which enforces safety and crew welfare standards. Many vessels in the dark fleet resort to flags of convenience or false registrations to evade inspection.

Venezuela’s regular dark fleet tankers are typically supplied by other countries, as Caracas lacks the financial means to maintain its own fleet and cannot depend on an existing fleet that is too small and outdated.

Top graphic: The tanker identifying as Freesia I recently indicated it would arrive in Venezuela by December 26, 2025.

Copyright 2025 Bloomberg.

Interested in Energy?

Get automatic alerts for this topic.