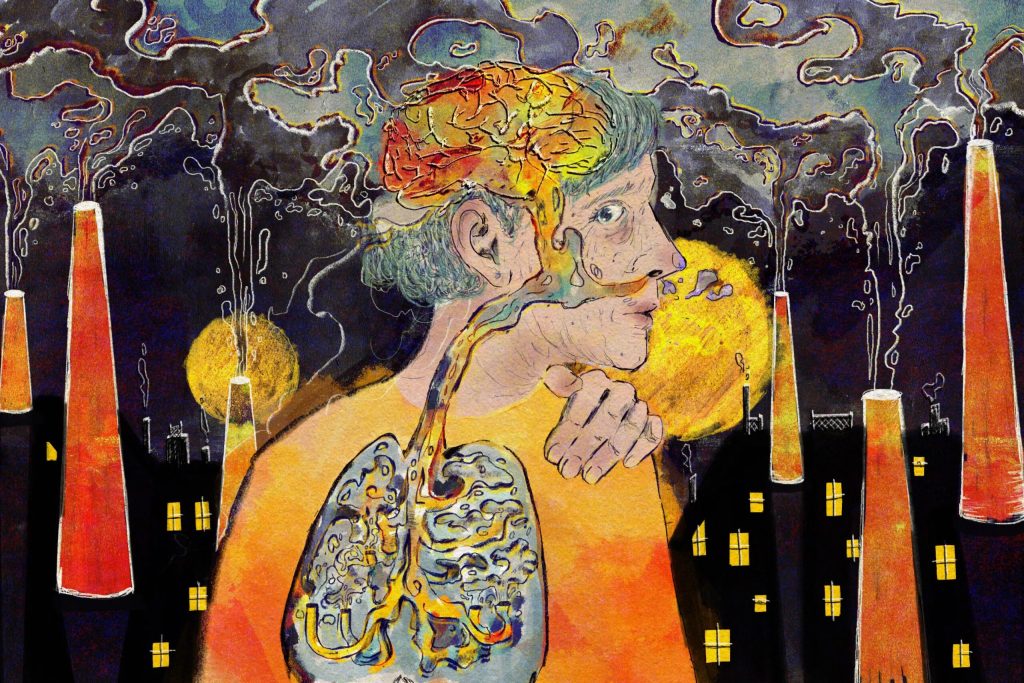

What the Air You Breathe May Be Doing to Your Brain

For years, two patients visited the Penn Memory Center at the University of Pennsylvania, where doctors and researchers monitor individuals with cognitive impairment alongside those with normal cognition.

Both patients, a man and a woman, had pledged to donate their brains for research after their deaths. “An amazing gift,” remarked Edward Lee, the neuropathologist who oversees the brain bank at the university’s Perelman School of Medicine. “They were both very dedicated to helping us understand Alzheimer’s disease.”

The man, who passed away at 83 with dementia, had lived in Center City, Philadelphia, with hired caregivers. An autopsy revealed significant amounts of amyloid plaques and tau tangles—proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease—throughout his brain.

In contrast, the woman, who died at 84 from brain cancer, “had barely any Alzheimer’s pathology,” according to Lee. “We had tested her year after year, and she had no cognitive issues at all.”

Geographically, the man lived just a few blocks from Interstate 676, which cuts through downtown Philadelphia, while the woman resided a few miles away in the suburb of Gladwyne, surrounded by woods and a country club.

The air pollution exposure for the woman—specifically, the fine particulate matter known as PM2.5—was less than half that of the man. Could this difference explain why he developed severe Alzheimer’s while she remained cognitively intact?

With growing evidence that chronic exposure to PM2.5, a neurotoxin, not only harms lungs and hearts but is also linked to dementia, the answer seems likely.

“The quality of the air you live in affects your cognition,” stated Lee, the senior author of a recent article in JAMA Neurology. This study is one of several recent investigations that demonstrate a connection between PM2.5 and dementia.

Scientists have been exploring this link for over a decade. In 2020, the influential Lancet Commission added air pollution to its list of modifiable risk factors for dementia, alongside issues like hearing loss, diabetes, smoking, and high blood pressure.

However, these findings emerge at a time when the federal government is rolling back efforts to reduce air pollution, moving away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources.

“‘Drill, baby, drill’ is totally the wrong approach,” commented John Balmes, a spokesperson for the American Lung Association and a researcher at the University of California-San Francisco. “All these actions will decrease air quality and lead to increased mortality and illness, including dementia.”

While many factors contribute to dementia, the role of particulates—microscopic solids or droplets in the air—is gaining attention.

Particulates originate from various sources: emissions from power plants, factory fumes, motor vehicle exhaust, and increasingly, wildfire smoke. Among the different particulate sizes, PM2.5 “seems to be the most damaging to human health,” Lee noted, as these tiny particles can easily be inhaled, entering the bloodstream and potentially reaching the brain directly.

The research conducted at the University of Pennsylvania represents the largest autopsy study of dementia patients to date, involving over 600 brains donated over two decades.

Previous studies primarily relied on epidemiological data to establish a connection between pollution and dementia. Now, “we’re linking what we actually see in the brain with exposure to pollutants,” Lee explained, emphasizing the depth of their investigation.

Participants had undergone years of cognitive testing at Penn Memory. Using an environmental database, researchers calculated PM2.5 exposure based on home addresses. They also developed a matrix to assess the extent of Alzheimer’s and other dementias in the donors’ brains.

Lee’s team concluded that “the higher the exposure to PM2.5, the greater the extent of Alzheimer’s disease.” The odds of severe Alzheimer’s pathology at autopsy were nearly 20% higher among donors who lived in areas with elevated PM2.5 levels.

Another research team recently reported a connection between PM2.5 exposure and Lewy body dementia, which is often associated with Parkinson’s disease. This type of dementia is generally considered the second most common after Alzheimer’s, accounting for an estimated 5% to 15% of dementia cases.

In what is believed to be the largest epidemiological study of pollution and dementia, researchers analyzed records from over 56 million Medicare beneficiaries from 2000 to 2014, comparing initial hospitalizations for neurodegenerative diseases with PM2.5 exposure by ZIP code.

“Chronic PM2.5 exposure was linked to hospitalization for Lewy body dementia,” stated Xiao Wu, a biostatistician at Columbia University and co-author of the study. After controlling for socioeconomic factors, the researchers found that hospitalization rates for Lewy body dementia were 12% higher in U.S. counties with the highest PM2.5 concentrations compared to those with the lowest.

To further validate their findings, researchers administered PM2.5 to laboratory mice, which exhibited “clear dementia-like deficits” after 10 months. Senior author Xiaobo Mao, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, noted that the mice struggled with tasks they previously performed easily, and their brains showed signs of atrophy and protein accumulation associated with Lewy bodies.

A third analysis, published this summer in The Lancet, reviewed 32 studies from Europe, North America, Asia, and Australia, finding a significant association between long-term PM2.5 exposure and dementia diagnoses.

Whether ambient air pollution increases dementia risk through inflammation or other physiological mechanisms remains an area for future research.

Despite a decline in air pollution in the U.S. over the past two decades, scientists are advocating for stronger policies to ensure cleaner air. “People argue that air quality is expensive,” Lee remarked. “So is dementia care.”

However, recent political shifts threaten to reverse progress. President Donald Trump has pledged to increase fossil fuel extraction and block the transition to renewable energy, rescinding tax incentives for solar and electric vehicles. Balmes noted, “They’re encouraging continued coal burning for power generation.”

The administration has halted new offshore wind farms, announced oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and moved to block California’s electric vehicle transition plan, which the state is challenging in court.

“If policy goes in the opposite direction, with more air pollution, that’s a significant health risk for older adults,” Wu warned.

Last year, under the Biden administration, the Environmental Protection Agency set stricter annual standards for PM2.5, acknowledging that “the available scientific evidence indicates that the current standards may not adequately protect public health.”

In March, the EPA’s new chairman announced that the agency would be “revisiting” these stricter standards.

The New Old Age is produced through a partnership with The New York Times.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

For years, two patients visited the Penn Memory Center at the University of Pennsylvania, where doctors and researchers monitor individuals with cognitive impairment alongside those with normal cognition.

Both patients, a man and a woman, had pledged to donate their brains for research after their deaths. “An amazing gift,” remarked Edward Lee, the neuropathologist who oversees the brain bank at the university’s Perelman School of Medicine. “They were both very dedicated to helping us understand Alzheimer’s disease.”

The man, who passed away at 83 with dementia, had lived in Center City, Philadelphia, with hired caregivers. An autopsy revealed significant amounts of amyloid plaques and tau tangles—proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease—throughout his brain.

In contrast, the woman, who died at 84 from brain cancer, “had barely any Alzheimer’s pathology,” according to Lee. “We had tested her year after year, and she had no cognitive issues at all.”

Geographically, the man lived just a few blocks from Interstate 676, which cuts through downtown Philadelphia, while the woman resided a few miles away in the suburb of Gladwyne, surrounded by woods and a country club.

The air pollution exposure for the woman—specifically, the fine particulate matter known as PM2.5—was less than half that of the man. Could this difference explain why he developed severe Alzheimer’s while she remained cognitively intact?

With growing evidence that chronic exposure to PM2.5, a neurotoxin, not only harms lungs and hearts but is also linked to dementia, the answer seems likely.

“The quality of the air you live in affects your cognition,” stated Lee, the senior author of a recent article in JAMA Neurology. This study is one of several recent investigations that demonstrate a connection between PM2.5 and dementia.

Scientists have been exploring this link for over a decade. In 2020, the influential Lancet Commission added air pollution to its list of modifiable risk factors for dementia, alongside issues like hearing loss, diabetes, smoking, and high blood pressure.

However, these findings emerge at a time when the federal government is rolling back efforts to reduce air pollution, moving away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources.

“‘Drill, baby, drill’ is totally the wrong approach,” commented John Balmes, a spokesperson for the American Lung Association and a researcher at the University of California-San Francisco. “All these actions will decrease air quality and lead to increased mortality and illness, including dementia.”

While many factors contribute to dementia, the role of particulates—microscopic solids or droplets in the air—is gaining attention.

Particulates originate from various sources: emissions from power plants, factory fumes, motor vehicle exhaust, and increasingly, wildfire smoke. Among the different particulate sizes, PM2.5 “seems to be the most damaging to human health,” Lee noted, as these tiny particles can easily be inhaled, entering the bloodstream and potentially reaching the brain directly.

The research conducted at the University of Pennsylvania represents the largest autopsy study of dementia patients to date, involving over 600 brains donated over two decades.

Previous studies primarily relied on epidemiological data to establish a connection between pollution and dementia. Now, “we’re linking what we actually see in the brain with exposure to pollutants,” Lee explained, emphasizing the depth of their investigation.

Participants had undergone years of cognitive testing at Penn Memory. Using an environmental database, researchers calculated PM2.5 exposure based on home addresses. They also developed a matrix to assess the extent of Alzheimer’s and other dementias in the donors’ brains.

Lee’s team concluded that “the higher the exposure to PM2.5, the greater the extent of Alzheimer’s disease.” The odds of severe Alzheimer’s pathology at autopsy were nearly 20% higher among donors who lived in areas with elevated PM2.5 levels.

Another research team recently reported a connection between PM2.5 exposure and Lewy body dementia, which is often associated with Parkinson’s disease. This type of dementia is generally considered the second most common after Alzheimer’s, accounting for an estimated 5% to 15% of dementia cases.

In what is believed to be the largest epidemiological study of pollution and dementia, researchers analyzed records from over 56 million Medicare beneficiaries from 2000 to 2014, comparing initial hospitalizations for neurodegenerative diseases with PM2.5 exposure by ZIP code.

“Chronic PM2.5 exposure was linked to hospitalization for Lewy body dementia,” stated Xiao Wu, a biostatistician at Columbia University and co-author of the study. After controlling for socioeconomic factors, the researchers found that hospitalization rates for Lewy body dementia were 12% higher in U.S. counties with the highest PM2.5 concentrations compared to those with the lowest.

To further validate their findings, researchers administered PM2.5 to laboratory mice, which exhibited “clear dementia-like deficits” after 10 months. Senior author Xiaobo Mao, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, noted that the mice struggled with tasks they previously performed easily, and their brains showed signs of atrophy and protein accumulation associated with Lewy bodies.

A third analysis, published this summer in The Lancet, reviewed 32 studies from Europe, North America, Asia, and Australia, finding a significant association between long-term PM2.5 exposure and dementia diagnoses.

Whether ambient air pollution increases dementia risk through inflammation or other physiological mechanisms remains an area for future research.

Despite a decline in air pollution in the U.S. over the past two decades, scientists are advocating for stronger policies to ensure cleaner air. “People argue that air quality is expensive,” Lee remarked. “So is dementia care.”

However, recent political shifts threaten to reverse progress. President Donald Trump has pledged to increase fossil fuel extraction and block the transition to renewable energy, rescinding tax incentives for solar and electric vehicles. Balmes noted, “They’re encouraging continued coal burning for power generation.”

The administration has halted new offshore wind farms, announced oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and moved to block California’s electric vehicle transition plan, which the state is challenging in court.

“If policy goes in the opposite direction, with more air pollution, that’s a significant health risk for older adults,” Wu warned.

Last year, under the Biden administration, the Environmental Protection Agency set stricter annual standards for PM2.5, acknowledging that “the available scientific evidence indicates that the current standards may not adequately protect public health.”

In March, the EPA’s new chairman announced that the agency would be “revisiting” these stricter standards.

The New Old Age is produced through a partnership with The New York Times.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).